top of page

WILLIAM EDEN NESFIELD,

1835 - 1888:

Architect

Born in Bath on 2 April 1835, was educated at Eton, and served his articles to William Burn [q. v.], architect, of Stratton Street, Piccadilly, and subsequently studied under his uncle, Anthony Salvin [q. v.]

He published in 1862 as the result of professional travel ‘Specimens of Mediæval Architecture, chiefly selected from Examples of the 12th and 13th Centuries in France and Italy, and drawn by William Eden Nesfield.’ The work, which is dedicated to William, second earl of Craven, comprises a large number of careful drawings of some of the finest French cathedrals, such as Chartres, Amiens, Laon, Coutances, and Bayeux. Among Nesfield's more important works were Kinmel Park, Denbigh; Cloverley Hall, Shropshire; the hall and church at Loughton, in Essex; Gwernyfed Hall, Brecknockshire; Farnham Royal Church, and lodges at Kew Gardens and Hampton Court.

Nesfield was also a great connoisseur and expert designer of all kinds of furniture. He was an admirable draughtsman, and, like his father, of an exceptionally versatile talent. He married, on 3 Sept. 1885, Mary Annetta, eldest daughter of John Sebastian Gwilt, and granddaughter of Joseph Gwilt [q. v.]

NORRIS GREEN HALL

The Norris family had an estate here in the fourteenth century, acquired by William, younger son of John le Norreys of Speke. (fn. 66) It descended in the fifteenth century to Thomas Norris, (fn. 67) whose daughter and heir Lettice married her distant cousin Thomas Norris of Speke, and so carried the estate back to the parent stock. One of their grandsons, William Norris, was settled here, his estate remaining with his descendants to the end of the seventeenth century. (fn. 68)

The family remained constant to the Roman Church and had to face loss and suffering in consequence, especially during the Commonwealth; (fn. 69) thus the threat of a fresh outbreak of persecution as a result of the Oates plot appears to have broken the resolution of 'Mar. Norris of Derby,' who conformed to the legally established religion in 1681. (fn. 70) Norris Green is supposed to indicate the site of their estate.

70. This was probably Richard, son of Henry Norris, aged 22 in 1664; Thomas Marsden, vicar of Walton, wrote in 1681 asking favour for him, as he was 'not yet cleared in the Exchequer for his recusancy and had heard his name was in the list of such as should have £20 a month levied upon their heads.

' Under these circumstances Mr. Norris's conformity 'to our church' was 'as full as it could be'; Kenyon MSS. (Hist. MSS. Com.),

His act does not seem to have saved the estates; the family disappear from notice, and much or all of the property is held by the representatives of John Pemberton Heywood, banker, of Liverpool.

From: 'Townships: West Derby', A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 3 (1907), pp. 11-19.

URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41281

Date accessed: 26 January 2013.

NORRIS GREEN HALL

John Pemberton Heywood- of Heywood’s Bank which became Barclay’s – ran a competition for young Architects to design a Memorial for West Derby Village in Liverpool.

The winner was W E Nesfield.

As a result of this win he was given the commission to design and build Heywood’s new home Cloverley Hall.

Original Signed Sketch Of Cloverley Hall

It is believed that it was as a result of this commission that he was brought to the attention of Hugh Robert Hughes.

Nesfield was asked to work on the Gate Houses located around the perimeter of the Park.

He then moved onto Home Farm - better known now as Kinmel Manor Hotel

Before starting on redesigning the poorly designed Thomas Hopper Building

Some people said the W E Nesfield was mad, some said he was a visionary. He created a Building that was stunning in looks and Ground Breaking in design

W.E.NESFIELD PLAN SHOWING 'SKELETON'

CLICK ON IMAGE TO MAGNIFY

He died at Brighton on 25 March 1888, and was buried there. A portrait was in the possession of his widow.

However,

'The Crown in his Career'

has plenty more surprises yet to unveil!

Especially if this is anything to go by: -

_JPG.jpg)

!NEWSFLASH!

WE UNDERSTOOD THAT KINMEL HALL WAS THE

ONLY

SITE THAT WILLIAM ANDREWS NESFIELD, ARTHUR MARKHAM NESFIELD AND WILLIAM EDEN NESFIELD ALL WORKED ON TOGETHER

WE WERE WRONG!

‘In 1861 the landscape designer William Andrews Nesfield, 1794–1881, received one of his most important public commissions; not only because the scheme is still in situ, impressively restored in 1996, but also because it is one in which all three Nesfields were involved and it was adjacent to the family home at 3 York Terrace. Apart from Nesfield Snr’s contribution, his eldest son the architect William Eden Nesfield (1835–88), designed a Lodge House to accompany the gardens and his second son Arthur Markham Nesfield (1842–74) was, after the first year, to provide the planting plans for the Avenue Gardens and also design an adjacent Picturesque Shrubbery.'

LOUGHTON GARDEN FRONT

LOUGHTON HALL

LOUGHTON GROUND PLAN

LOUGHTON GARDEN FRONT

1/24

WILLIAM EDEN NESFIELD,

1835 - 1888:

BY J.M.BRYDON, ER.I.B.A.

It is somewhat surprising that though nine years have passed away since William Eden Nesfield's death, beyond the briefest obituary notices, no account of his

work has, as yet, appeared. This is all the more remarkable because, not only was he a great Artist in himself, but his influence on the contemporary work of his day was second only — if that — to his friend Mr. Norman Shaw. Indeed, all during the " sixties " their names were so linked together, their published sketches from the Continent so similar in character, their work so wonderfully alike in design and intention, the conjunction Nesfield and Shaw so familiar in the

artistic world, that it hardly ever occurred to Architects to think of them separately, and yet in spite of a brief partnership in the earlier days of their practice, they never really did a joint work.

They shared offices and studies, had the same high

aims and aspirations, the same keen artistic instincts ; good comrades both, but each devoting himself to his own especial work ; advancing along separate yet parallel lines in all that made for the culture and ennobling of the Art they mutually loved, and whose highest interests they did so much to promote.

William Eden Nesfield may be said to have come of an artistic stock ; his father, Major Nesfield, besides being a well-known member of the old Society of Painters in Water Colours and a constant contributor to its exhibitions, became famous in his day for his facility in designing and laying out ornamental gardens, terraces, and parks. He had the happy gift—inherited also by his distinguished son—of making the mansion house and its surroundings part and parcel of the same design,

inter-dependent one upon the other for the harmony

of the result he sought for and secured.

To Major Nesfield we owe the gardens in Regent's and St. James's Parks, the re-modelling of those at Kew,

and at many noblemen's seats all over the country. He had a keen eye for architectural effects and may be said to have been the reviver and restorer of the old formal garden, the value of which as an accessory of domestic Architecture is now again admitted to be of the first importance. William Eden, the major's eldest son, was born on the 2nd of April, 1835, and was educated at Eton.

He never forgot the famous School, and to the last was proud of his Alma Mater. Who can say how its associations, historic and otherwise, responded to or called forth the artistic instincts of the boy at the most impressionable time of his life ; to its influence also he doubtless owed much of the uprightness and independence of his character, his quick sense of honour, his desire to " keep his shield bright," as he enthusiastically phrased it, declaring that if Eton did not produce great scholars at all events it turned out gentlemen; by birth and education, therefore, he was essentially the latter whatever his claims may have been to the former. How high his ideal was in this

respect may be gathered from his facetious remark

that old Professor Cockerell was the only gentle

man in the profession.

After Eton came the question of his life's vocation ; a happy fate decided for Architecture, though his introduction to the mother of all the Arts was somewhat chequered. First of all he went for a few months to Mr. J. K. Colling " to learn to draw"; then afterwards, in 1 851, he became an articled pupil with the late Mr. Burn. Mr. Norman Shaw was also a pupil in the office at this time, though the two met first at Major Nesfield's house at Windsor.

Somehow the work in Mr. Burn's office proved

uncongenial, he could not or would not take kindly

to it, the result being that after a couple of years he

left and entered the office of his uncle, Mr. Antony

Salvin, where he remained till the midsummer of

1856, going downtoKeele Hall, in Staffordshire—a

large house Mr. Salvin was then building—for some

months, to be under the Clerk of Works. He was

then only twenty-one, and it must be remembered

at that time the Battle of the Styles was in full progress. Mr. Burn may be said to represent the classic, and Mr. Salvin the mediaeval side of the question, and the Gothic revival, then in all its fervour, carried the young student along with it.

Having " learned to draw " very well, getting through

his articles somehow, and seeing a little of practical

work on a building in progress, he went off on a foreign

tour, and to study in France, Italy, and Greece. He did

much travelling, doubtless much observation, and a fair

amount of sketching; on his return, finding Mr. Shaw at

work on his well known book, he was persuaded into following his example, but not having enough material for the purpose, set off again, this time principally to France, to make the sketches and measured drawings, after wards published. The two volumes became the text books of the Gothic revival, and brought their

authors into the most prominent notice, not only as

skilled draughtsmen, but as leaders in the movement.

These books were marvels of Architectural delineation, and, what is more, could be thoroughly depended

upon for accurate information. As Mr. Nesfield himself wrote : " My endeavour has been to faith fully represent the subjects as I saw them, avoiding, with few exceptions, such as had been touched by restoration, a process which, as at present conducted in France, frequently tends to destroy the character of the old work." Most of the illustrations in his book were drawn on the stone by himself, and the initial letter on the title page is probably his first published design, the figures on the same page being drawn by his friend, the late

Mr. Albert Moore.

The period of probationary study being over, Mr. Nesfield settled down to work in Bedford Row in 1859, his first important commission being a new

wing to Combe Abbey for Lord Craven, the nobleman to whom he dedicated his book of sketches.

In 1862, on going into partnership with Mr. Shaw, he removed to No. 7, Argyle Street. As already said, the partnership was purely nominal, and lasted but a few years, though they shared offices together till 1876, when, the premises being required for other purposes, Mr. Nesfield migrated to No. 19, Margaret Street. His room in Argyle Street was a sight in those days, containing as it did a valuable collection of blue and white Nankin china and Persian plates, Japanese curios, brass sconces and other metal work, nick-nacks of various descriptions, and a well stocked library, in a case designed by himself. It was the studio of an artist, rather than the business room of a professional man ; any samples of building materials being conspicuous by their absence. How proud he was of his Persian plates, and how enthusiastic over the flush of the blue in his hawthorn jars, or the drawing of the "Long Eliza's" on his

six mark dishes, only those knew who were privileged to hear him discourse thereon ; at that time the Japanese craze had not broken out into an epidemic, and, as yet, " Liberty " as such, existed not, but Nesfield knew all about the movement; he could estimate Japanese Art at its true value, and its place in the grammar of ornament, not hesitating to introduce the characteristic discs and key pattern into his work when occasion served. One loves to think of him amid the

congenial surroundings of his room in Argyle Street, working away at the Art in which he delighted, within converse of his friend Shaw, and looked up to with enthusiasm by his fortunate assistants, as the man at his best ; a memory that will never fade away.

Here the principal works of his life, such as Combe Abbey, Cloverley Hall, and Kinmel Park, were carried out, here o' nights would come his artistic friends—the Painter, the Sculptor, the Poet—and with inspiriting intercourse stimulate each other to higher and nobler efforts. The warm hearted geniality of his nature

was infectious ; his kindly counsel, and the brilliant example of his conscientious work, both as a designer and a draughtsman, were the highest encouragement to all who came under his influence.

Men whose names are now well known in their Profession look back to those days with a feeling of thankfulness akin to gratitude that they were privileged to study under such a consummate master of his craft.

It is no part of the writer's intention to estimate the value of Mr. Nesfield's work or classify its standing in the history of nineteenth century Architecture in England, but rather to present such characteristic examples as shall serve to show the versatility of his genius, the wide range of his subjects, and the technical knowledge and artistic skill he brought to bear in carrying them out. He was a master of planning and of construction, no detail was too small for his attention ; difficulties arose only to be solved, and that too in the simplest and most practical manner. He had a keen eye for the picturesque, and yet never lost sight of the dignity of his work, be it a cottage or a mansion. Nor was there ever any straining after effect for effect's sake ; all grew naturally out of the requirements.

No one knew better than he the value of mouldings and ornament, drew them better, nor used them with more discretion. It was a pleasure to see him drawing out a full-sized detail for some elaborate piece of wood or

ironwork ; every line instinct with life, and carried out with a thoroughness and vigour which were all his own.

He had the true inwardness of decorative art, knowing when to use, and what is often of much greater

importance, when to refrain from, ornament.

As a result, in his work there is an absence of fussiness and a sense of quietude and dignity which is at once its strength and his reward.

For convenience sake, and without attempting any strictly chronological order, it is proposed to consider—firstly, his cottages and lodges; secondly, his mansions ; and then his churches, with one or two works which, perhaps, hardly come within either category.

Nothing was more characteristic of Mr. Nesfield than his cottages and lodges. He took a pride in these little structures, and was one of the first to show how artistic, and yet so convenient withal, a labourer's cottage

or a gate-keeper's lodge could be made. The lodges in Regent's Park, built in 1864, and in Kew Gardens, built in 1866, are landmarks in the history of such buildings. The former, bringing with it a whiff of the breezy weald of

Surrey into the heart of London for weary eyes to rest on, was a revelation in red brick, weather tiles, and stamped plaster. It never seems to have been thought of before, yet here it is, no tentative effort either, but a complete little gem. As for the lodge at Kew, with its cut brick pilasters, high-pitched roof, tall carved chimney, pedimented dormers, plaster cove, and classic detail, it is a bit of fully-fledged " Queen Anne," as it was called in those days—thirty years ago, be it remembered—when the Architectural world was still blindly floundering in the throes of the Gothic revival, the predominant note of the hour being Early French — a type on which Mr. Nesfield himself was then actually designing his work at Combe Abbey and Cloverley. Yet even at this initial period of his career he was quick to perceive the limitations of this early Gothic work ; the Lodges at Regent's Park and Kew were the beginning of the end of the then fashionable craze, the first notes of a change which was presently to bring about such works as Loughton Hall and Kinmel Park.

Beginning with the cottage, the movement soon overtook the Manor and the Hall, the leading idea being that all should be thoroughly English, in the letter no

less than in the spirit. Anglo-French was tried and found wanting, Anglo-Spanish we were mercifully spared, so the revival under such masters as Nesfield and Shaw settled down to be English first, whatever else it might be in addition.

On similar lines were his cottages at Crewe Hall, Hampton in Arden, and Broadlands, and the school at

Romsey. His autograph sketch for one of the Broadlands Lodges is here given ; but even more

characteristic than either of these, perhaps, is the

Gate Lodge at Kinmel Park, a truly delightful bit of

English Renaissance.

In all these charming little houses there is a freshness of design and an adaptability to their purpose which mark the hand of the true artist. The days of the little Greek temple standing at the entrance to an Englishman's park, and the pointed windows and sham battlements

of the Gothic with a " k " period, are over and gone, and the place thereof shall know them no more.

From the Gate Lodge we naturally find our way to the mansion. As early as 1862 Mr. Nesfield was busy with his first important work—a new wing at Combe Abbey for Lord Craven.

Fresh from his studies in France, and doubtless swayed by the impulses of the day, it was hardly to be wondered at that Combe Abbey showed a marked Earlv

French feeling throughout. As such it is certainly clever; as such it is just as certain that a few years later it would have assumed an altogether different character. It forms one side of a quadrangle. Two of the other sides—the main body of the house and a wing—are in a somewhat late, not to say debased, type of Elizabethan. The result is a jarring contrast, incongruous to a degree, and quite out of sympathy with its surroundings. For all that, there

are, as might be expected, exceedingly clever bits

of design—for example, the treatment of the end next the moat, with its boathouse and turreted angles. It is built of stone, with a slated roof, and, given the style, is most carefully worked out in detail, not, perhaps, with the thoroughgoing method of Purges, the apostle of Early French, but with a keen appreciation of its capabilities and—its limits.

That he soon became impressed with these limits is

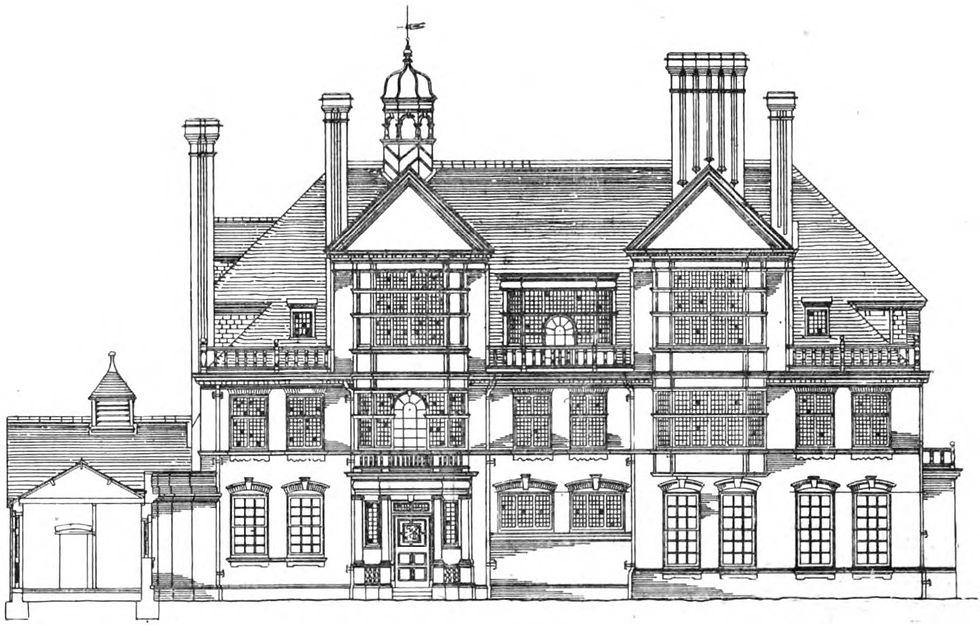

apparent in Cloverley Hall, designed in 1864 when he was only twenty-nine—for Mr. Pemberton Heywood, which, though still founded on a French model, is distinctly an English country house.

The plan of Cloverley is remarkable, and may be

studied with profit and advantage. The essentially

English feature of the Great Hall is introduced with conspicuous success. The house is built on a sloping site, so the treatment of this Hall, its place in and relation to the other portions of the general scheme, with the clever arrangement of the different floor levels, is worthy of all praise.

Mark the approach from the Great Hall to the principal staircase, and the skillful treatment of the latter as it rises to the first floor. Few modern mansions can boast such a dignity of entrance, such a clever adaptation of traditional features to modern requirements and the exigencies of the site.

Never afterwards, perhaps, did Mr. Nesfield plan anything better than Cloverley.

It was his first great opportunity, his genius rose to the

occasion, he seems to have thrown all his youthful

enthusiasm into the task, and worked at it as a labour of love.

The illustrations will serve to give some idea of the general Architectural character of Cloverley, the effect of which Mr. Eastlake gives very succinctly in his

"History of the Gothic Revival."

" Externally the house possesses, in addition to the

general picturesqueness of its composition, many distinctive characteristics of construction and design.

The bricks of which the main masses of the walls an; built were manufactured expressly for this building on the estate, and are far thinner than usual. They are laid with a thick mortar joint, resembling the style of work in old houses of the time of Henry VIII. The parapets—about 3ft. high—are of wood, covered with lead, which is beaten outwards at intervals in the form of large

rose-shaped ornaments, quaintly intersecting each other. Above this parapet on the main (or garden) front rise lofty dormers, bearing in their gables sculptured representations of the seasons, carved by Forsyth from designs by Mr. Albert Moore.

The effect of these figures, which are about two-thirds

of life-size, and are executed in very low relief, is very striking. . . . The whole nature of the Design, refined and skillful as it is, may be described as the reverse of pretentious. Its graces are of a modest, unobtrusive kind. The work is homely rather than grandiose, and though it bears evidence of widely-directed study, it certainly derives its chief charm from its unmistakably national character."

Internally the house is remarkable for its thoroughly artistic treatment—its oak panelling, rich plaster ceilings, magnificent stained glass in the bay window of the Hall, and in the staircase, and its sumptuous chimneypieces—that in the Great Hall having carved subject panels from Esop's fables, executed by Mr. Forsyth. The oak screen supporting the music gallery in the Great Hall is also richly carved, and it is noticeable that here as elsewhere in the woodwork the motif of the decoration is of a distinctly Japanese character, so cleverly adapted that there is no sense whatever of any impropriety.

The touch of the master's hand brings all into a delightful harmony. About this time also Mr. Nesfield was engaged on humbler, but in its way no less remarkable, work in the farm buildings at Shipley Hall, near Derby, and at Croxteth Park, near Liverpool, the features most worthy of note in each case being the dairies, the ceilings of which are enriched with decorative paintings by Mr. Albert Moore, who also designed the figures which enrich the fountain in the latter.

The general design of these works may be said to have been influenced by the Gothic revival, but Architecturally they were quite as much a revelation, in their class, as the little lodge in Regent's Park was in its, and the parallel also holds good still further as between the lodges and the mansions, for just as Mr. Nesfield designed the Queen Anne Lodge at Kew immediately after the one in Regent's Park, so Cloverley Hall was still in progress when, in 1866, he began the design for his great English Classic House at Kinmel Park, the two styles running concurrently, as it were, in his mind at this time.

Kinmel was not an entirely new house like Cloverley,

but extensive additions and alterations to a somewhat

unpretending example of eighteenth century Classic.

The additions, however, proved in the end of such importance that the place is almost a small Hampton Court in its way—indeed Nesfield's enthusiasm for this revived Classic, of which he was a pioneer, ran away with him to such an extent that the first design for Kinmel, when it came to be estimated for, proved too

costly, so it had to be reduced and done all over again, much to his regret, and to that of everyone who saw and could appreciate so masterly an achievement.

As it stands, however, Kinmel is a splendid house, treated with a broad and dignified grasp of the subject, a sense of proportion, and a skill in detail unrivalled by any of its contemporaries.

It is built of red brick, with stone dressings, and grey-green slates for the roof. The chapel is a noteworthy feature in the garden front, and it can be seen at a glance that it is the domestic oratory of a great country house, and does not ape a church-like effect. The same refinement of decorative detail prevails at Kinmel as at Cloverley.

The interior is rich in panelling, in plaster work, and in chimney-pieces. The hall fireplace is specially noticeable for the splendidly decorative effect gained by the panels of the overmantel, which reaches to the ceiling, being enriched with carved shields with their quarterings emblazoned in their heraldic colours ; the result is very striking indeed.

The two great mansions of Cloverley and Kinmel stand out as the typical examples of Mr. Nesfield's country houses, so different in style, a contrast in Design, yet a harmony in Art. Others followed, such as Farnham Royal House, near Slough ; Lea Wood (not to be confounded with Leys Wood by Mr. Shaw), Loughton Hall, and Westcombe Park, near Greenwich.

The types varied, now leaning to the sixteenth century Manor House, and again to the so-called Queen Anne, but all characteristically English, and not to be mistaken for anything but what they are— English Country Houses. The multitude of charming features scattered through these Designs is amazing ; their variety is seemingly endless. Take, for example, the chimney corner or ingle nook. We have them of all kinds, from the sumptuous to the homely, and yet all are homely.

As Mr. Eastlake says —

"There is, perhaps, no feature in the interior of even an ordinary dwelling house which is capable of more artistic treatment than the fireplace of its most-frequented sitting room, and yet how long it was neglected ! . . . How picturesque and interesting an object a fireplace may become when Designed by an Artist's hand."

There is a very striking example of a chimney corner in Mr. H. Vallance's house at Farnham Royal. " To draw round such a cosy hearth as this," says Mr. Eastlake, "is rarely given to modern gossips." Alas ! that this delightful feature has become so much abused in these latter days that it has degenerated into a fireplace in a recess, to be bought in the furniture shops as a " cosy corner."

That is not an ingle nook in the Nesfieldian sense, and never will be. As with his chimneypieces, so with other features ; his staircases how quaint in plan and design; his bay windows how restful ; his woodwork how carefully studied for its place and purpose. No detail was too unimportant or to be passed lightly over. All must be worked out to satisfy his fastidious taste.

Take his tall chimneys and half-timbered gables: in the

former we have every variety, both in plan and

Architectural treatment ; he loved to picturesquely

group them together, enriching them with cut brick

mouldings and carved panels— at that time almost unheard of—and in his half-timber work we have the true spirit as well as the letter of the best English examples. The enormous advance in all that makes for excellence in the planning and design of our modern country houses is the best tribute to the influence men of genius, such as Nesfield and Shaw, have had on its development, and on the ultimate result, till now, at the end of the nineteenth century, we have a domestic Architecture unsurpassed for its high and artistic qualities by that of any other country in the world.

The home is a peculiarly English institution, and certainly no houses, be they stately or be they humble, express the feeling of homeliness more truly than those of England.

The employment of heraldry as a decorative feature is another trait of Mr. Nesfield's work, and one he used with rare skill and judgment. We see it in most of his buildings, both externally, in panels, gables, and chimney stacks ; and internally, in chimney pieces, ceilings, and windows. One of the earliest examples of the former is in the tall chimney of the lodge at Kew Gardens, where the Royal Arms, carved in red rubber bricks, are quaintly introduced as a panel among the upright moulded ribs of the stack ; the effect is a striking as well as novel decorative feature. A particularly rich internal example is the treatment of the chimneypiece

and over-mantel in the hall at Kinmel Park, already mentioned. As will be seen from the illustration of this hall, the whole space between the mantel-shelf and the ceiling is covered with a series of carved panels, filled with coats of arms, which are emblazoned in their proper colours—a great family tree in fact, resulting in a splendid piece of decoration, full of interest, no less for

its architectural than for its heraldic treatment.

Only an artist thoroughly conversant with the subject could venture on such a display as this, and come out of it successfully.

In like manner he shows us what truly appropriate

Decoration can be got out of a family crest, or the

quartering of a shield, employed as emblems, and

used alternately with an initial or monogram as a

diaper, as may be seen, in conjunction with the full

achievement on the lodge at Kinmel Park, and on the drawing room chimney-piece at Cloverley Hall.

When one thinks of the splendid effects obtained by the Mediaeval and Renaissance builders by the use of heraldry and emblems, it is somewhat surprising Mr. Nesfield's lead in these respects has not been more often followed. In the more familiar adornment of hall and staircase windows with heraldic glass, we have many fine examples through out his work, notably the great windows in the staircase and hall at Cloverley.

As has been said, it is extraordinary that more use has not been made of heraldry in a decorative sense. For some reason or another, there seems to be a passive dislike to its employment, difficult to understand. After all it was, and is, only a family mark or emblem, to distinguish one from another, and yet a man who may have a decided aversion to the use of a coat of arms, will, at the same time, be exceedingly exacting in the use of a particular trade mark, and very zealous in the defence of his exclusive right thereto.

The inconsistency of such a position is somewhat inexplicable. Surely a man may be allowed as much personal identification with his family as with his calling, without laying himself open to the charge of any false

pride in either ; and what more appropriate Decoration can he have in his home than the badges or emblems that connect him with those of the kith and kin who have preceded him ?

It has to do with his personality, with who he is, as well as with what he is; and, apart from its historical interest, seems a matter for remembrance rather than neglect.

Analogous to Kinmel and Cloverley are two urban

examples of Mr. Nesfield's work, at Saffron Walden, in

Essex, where we again have the two distinct types standing side by side.

First there is The Bank, built in 1873, and designed quite in his earlier method, if one may use such a term.

It reverts to the mediaeval in style, the semi-public

character of the building being emphasized by the great mullioned windows of the banking-room on the ground floor. Unfortunately the front was not carried out as originally designed. It was intended to be finished by a lofty gable, but there seems to have been some fear it would prove too high for the position ; it was, therefore, reduced, and one of his favourite leaden parapets, with a dormer behind it, substituted for the gable—a matter for great regret.

The banking room, just referred to, is a fine apartment, 32ft. long by 28ft. wide, and 20ft. high, lighted by the large mullioned windows in the front. It was designed with high panelling all round the walls, with a frieze above, a fine fireplace, and a richly panelled ceiling, investing it at once with the dignity befitting its purpose. Next door to the bank is the Rose and Crown Hotel, to which Mr. Nesfield built a new Queen Anne front, quite,

in keeping with the traditions of the old hostelry, quiet and unostentatious in feeling, its red brick, stamped plaster, and white painted window-sashes seem to invite a welcome to the hospitality within.

The fine town mansion, No. 26, Grosvenor Square, was almost entirely re-modelled by him for Mr. Heywood-Lonsdale in 1878. It is chiefly remarkable again for its fine oak panelling, its rich plaster ceilings, its charming chimney-pieces, and its very cleverly designed conservatory, all bearing both the plan and elevation are full of interest, especially the former. It appears the work was subsequently done, but not under his direction, and, of course, to quite another design.

The chapter of Mr. Nesfield's church and school work is but a short one. He never seems to have built a large and important church, but rather restorations and rebuilding. Of the latter, St. Mary's, Farnham Royal, near Slough, is a typical example. It was begun in 1867, and is carried out mainly on the lines of the old church. The walls are of flint, and have courses of tiles built into them

The impress of his skill in clothing with interest and beauty the everyday features of a gentleman's house. A special feature is the smoking room, which has a barrel-vaulted ceiling enriched with very good decorative plaster work, and a quaint fireplace, a cosy, comfortable room, in which to spend a pleasant hour in pleasant chat.

Like many other Architects, Mr. Nesfield's designs were not always carried out. His scheme for the alterations and additions to Gregynog Hall in North Wales seems to be one of these, but as bonders, in Roman fashion, and showing externally. He was very anxious to preserve the west tower, but its condition was such that it had to go at last, and was rebuilt some years later than the rest of the church.

The style is Early Decorated, and the church has a nave and aisles, chancel, and west tower. The mouldings of the piers and arcades, and the tracery of the windows, are drawn with extreme care. The chancel arch is noteworthy for the peculiar outline of its curve, and for the detail of the responds. Over the door from the chancel to the vestry, and at other places, are some of the carved discs Mr. Nesfield was so fond of introducing

" pies," as he familiarly called them sometimes intersecting each other, and again at regular intervals, just as they happened to come in.

Farnham Royal Church has an ideal site for a village

House of Prayer, and is surrounded with some fine

trees.

The restorations of King's Walden Church followed in 1868, and Radwinter Church in 1871. King's Walden Church, near Hitchin, was a restoration pure and simple, though the chancel was nearly rebuilt in the process. The clerestory of the nave was also refaced, the parapets rebuilt, and the windows almost renewed. The walls are faced with flints, and the dressings of the doors, windows, buttresses, etc, are of stone. The south porch, of open timber, with its tile roof, is new.

The church is Late Gothic in style ; nearly all the internal fittings are new, except the very interesting chancel screen, which was most carefully restored. As will be seen from the plan, the chancel is large for a church of its size —nearly as long as the nave, and not much narrower—and has an interesting chapel on its north side. All the fittings of the chancel, together with the pulpit, reading desk, etc, are most characteristically designed and carefully carried out. The church, as will be seen from the view, has again a fine site. The west tower remains untouched, and is a striking feature in the composition.

Radwinter Church, near Saffron Walden, in Essex, was an enlargement as well as a restoration.

The nave was lengthened eastwards by one bay, and the chancel and vestry designed and built by Mr. Nesfield ; the old chancel arch and the eastern responds of the nave arcade being re-used in the new work. The style is Middle Pointed ; the walling is faced with flints, with stone dressings, as in the two previous churches, and the same care is noticeable in the detail of the mouldings and in the window tracery throughout.

The roof over the nave is a fine open timber one, and the new portion east wards is carried out exactly similar to the old work) both over the nave and the aisles.

Nothing could exceed the thoughtfulness, the truly conservative spirit, and the sincere regard for the original work, with which these restorations have been carried out ; every bit of the old work that could be saved was carefully preserved and re-used, such as the

credence and the sedilia at Radwinter, which are refixed in the south wall of the new chancel. The stalls and other fittings there are new, and Mr. Nesfield not only designed the organ case, but wrote the specification of the new organ itself. So sure was he of his musical knowledge of his subject that he peremptorily forbade the alteration of any of the stops or pipes without his permission.

Reasonable men, Architects have to face all these requirements in a reasonable manner—as Artists rather than as engineers, and with a full sense of their responsibilities as well as their opportunities.

That the former are as heavy as the latter are sometimes alluring can never be absent from the mind of anyone who approaches his task with that reverence of feeling which must be one of his first qualifications. It is not only a matter of archaeology, or even of construction, but of the knowledge and skill of architectural conservatism, and the experience which comes of them all. An Architect's responsibilities are never light at any time, least of all when a historical monument

He also restored Cora Church, near Whitchurch in

Shropshire, designing for it a new reredos. Restoration, as we have had reason to know lately, is a very vexed question, but when it becomes a choice of preserving or losing altogether such charming old churches as the foregoing, it is a matter for thankfulness when they fall into the hands of a conservator like Mr. Nesfield.

Repairs must be done if the fabric is not to go to ruin ;

enlargements must sometimes be made if the growing needs of a parish are to be satisfied, and the circumstances will not allow of a new chapel of ease to the Mother Church—and, as is entrusted to his care to save from the past for the benefit of the future, and the credit of the present.

The Grammar School at Newport, in Essex, and the Boys' School at Romsey, in Hants, fairly represent Mr. Nesfield's contributions to educational purposes. They were built in the pre-School Board days, and are quite in his well-known manner. The Newport School, with its little Quad, its great Schoolroom, Dining Hall, Dormitory, and Head Master's Residence is most picturesque in its grouping, and admirable in plan.

The feeling of all being shut in within itself as it were, is eminently suggestive of the seclusion one associates with study, while its quaintness architecturally is still reminiscent of the home. It is astonishing how Nesfield always managed to embody the peculiar qualities of the purposes to which his buildings were devoted, making their outward semblance so easily proclaim their import,

that he who runs may read.

It is much to be regretted that we have no public building from the hand of such an artist as Mr. Nesfield. Though there is a tradition that he sent in a Design in competition for the Manchester Assize Courts, we never hear of him again seeking such an opportunity of distinguishing himself.

Perhaps his possession of independent means,

which left him free to choose his own path, in

directly contributed to this by depriving him of the

necessity of engaging in any such speculative and,

to him, probably uncongenial work. Perhaps, also,

we owe to the same cause the less extended exercise of his great genius in the more public walks of

his profession. Be this as it may, it is remarkable

in his case, as in that of others, that a great Artist

should have been allowed to pass away without being given the opportunity of enriching his country with any public monument.

Surely in England only is such a state of things possible.

The State, or other public bodies, seem to think that only in the rush of competition are they likely to secure great buildings, forgetful that it is more than possible the most highly-gifted of our Architects not only never enter the lists at all, but refrain, from the conviction that it is in this method they can do themselves justice, or even that great works of Art are produced.

Again, Mr. Nesfield, although he was an Associate of the Royal Institute for a few years in his younger days, never seems to have given his professional brethren, in their corporate capacity, the advantage of his counsel or experience in matters of mutual interest. He never attended meetings, made speeches, or wrote papers. Indeed it is said, an idea that he was expected to do something of the kind at Conduit Street, led to the resignation of his membership of the Institute. But he was a member of the Foreign Architectural Book Society familiarly known as the F.A.B.S.—the social side

of which doubtless appealed to his ardent temperament, and met with a ready response.

On the burning questions of the day, or what may be called the politics of the profession, it is not difficult to

guess the side that Nesfield would have taken, or to

imagine the fine scorn with which he would have

laughed at registration, and examination, and other

shibboleths of latter-day Societies.

He had a very strong belief that Architecture was an Art, whatever it might be worth as a profession, that, unlessa man was an Artist he was no Architect at all, and had much better become a Builder, with some hope of driving about in his brougham, than struggle on in the endeavour to manufacture buildings at five—

or less—per cent.—to the detriment of the fair

fame of Art and his own probable loss profession

ally. Yes, it is much to be feared Nesfield would

have been a " Memorialist " of the deepest dye,

with a healthy disregard for the pretensions of our

friend, the " Progressive," or any dictation from

him or his like as to what an Architect should or

should not be, or any Society that sought to forbid

any man from working at his Art as he thought

best. The one test with Nesfield was, Could he do

it ? If so, well and good, he is a Fellow and

a Craftsman—if not, well again, and—the less said the better—but it was sure to be forcible, and very much to the point. In private life he was always entertaining, numbering some of the most eminent men in Art and Letters among his friends. In his professional capacity, as one writer said of him, " Among his strongest characteristics were a singular uprightness and a sturdy independence in his bearing towards his clients. He never could be persuaded that he was the servant

of an employer, and treated him in something of the same manner as Michael Angelo treated Pope Julius—as a friend and patron and nothing more."

Of his work, as of himself, it may be truly said, one of the chief characteristics is its sturdy in dependence. He copied no man, followed no school, but struck out a path for himself. A leader rather than a disciple, he showed the way by which, without forgetting old traditions—and especially English traditions—the Architecture of our time can still be made—and is—a living Art, that to be original it is not necessary to forget the teaching and example of the past of any age, that to be picturesque it is not essential to be either restless

or even willfully irregular ; that if, in the first place, our houses must be convenient, that is no reason why they should not be beautiful within and with out, dowered with the quiet dignity, and pervaded by the repose of the home life so dear to our English race. It may be that, as yet, the Art of Nesfield is too close to our own day to enable us to appreciate its true value in the development going on during his time and since, its place in the revival, not of this style or of that, but of faith in and knowledge of the great and everlasting

principle of designing with truth and building with

beauty ; such introspection may, perhaps, become the duty as well as the privilege of the historian of the Architecture of the Victorian Age ; but assuredly we must recognise, and in recognising acknowledge, the inwardness of the true artist in all that he did, in its Design no less than its accomplishment.

Though never losing sight of the fact that Architecture in its very essence is first and fore most a constructive Art, Nesfield never forgot its decorative aspect ; the claims of beauty, as such, whether in form or in colour, seem to have been ever present to his mind, and no one was more ready to call to his assistance the painter and the Sculptor, so that labouring together as fellow Craftsmen they might attain to a more glorious result.

WILLIAM EDEN NESFIELD

BY

DAVID BURTON

CLOVERLEY

William Eden Nesfield was an English architect who had had a lot to do with Shaw. I believe he and Shaw went to Europe to do their Grand Tour and came back with all sorts of ideas and wrote a book together describing their findings. Later Nesfield tried to reintroduce what he called The English Style, going back to Elizabethan and Tudor buildings built with small red bricks, blue brick patterns, tall elaborate chimneys and sandstone mullioned windows.

I understand his father, William Andrews Nesfield, was an army man although he became a great landscape gardener. I understand his son might have got some of his commissions through his father's contacts. One of his father's better known gardens are the gardens at Witley Court in Worcestershire with its huge fountain representing Perseus and Andromeda which when running was described as sounding like an express train when fired.

I suspect that William Eden's dislike of symetry might have been a rebellion against the strict regimentation in the army!

When he was a boy he lived in Windsor and went to Eton School. In many of his buildings he replicated a tower in the outer wall of Windsor Castle. At Cloverley his semicircular tower housed the gunroom on the ground floor, the game room where they hung the carcases of meat, game, and above that he built the dove cot. The game room was double walled with air vents slitted into the outer skin and so creating a cold room. He had numerous inovations including a slate cold chest where ice and salt would have been put in order to preserve the food which was also put in there, but also for the sillabubs which were popular with Victorians.

Certainly at Cloverley he created a pool, shallow and broad which would produce the ice necessary for his ice box. He also build two ice house, one at either end of the lake, below ground, and I believe there was an underground passage to the house some 300 yards away. Other inovations were the collection of water off the roofs in catch boxes covered over with sandstone lids and a separate drainage system took the clear water away from the boxes into two large chamber some 10ft by 10ft and 6ft deep under the laundry room. From there the water was pumped up by hand into the tanks in the roof which was then used by washing, laundry, giving to the horses etc, whilst drinking water for the kitchen was provided by a beautiful brick lined well over a spring. This water too was pumped up to the tank in the kitchen, (all tanks were lead lined wooden boxes.)

His architectural style was distinctly non symmetrical with little variations in the windows, the moulding of the sandstone mullions, the size and shape of the brickwork either side if the windows had gables over them. Each finial was different but usually displaying a flower head on the top, carved in Shropshire sandstone. The bricks were small, and hand made from clay in the surrounding fields. As with most houses of that era the best bricks were used at the front whilst the poorer bricks were used at the back. Sadly at Cloverley the bricks at the back have been erroded by wind and the acid in the horses' urine. We have had to reface much of the brickwork.

He used vertical damp proofing by building retaining walls around the building where he had rooms below ground floor level and capped off the air gaps created with sandstone slabs. His roofs were indicative of French influence. They were steep, using graded slates, and belling the roofs to slow down the rain as it fell so that it did not overshoot the roof gutters.

Cloverley Hall, like Kinmel, was a calendar house, paying tribute to the change from seasonal time to factory hooter time. The seasons, and the months of the year were carved into sandstone squares round the clock and round the frieze work below the roof level at Cloverley. I understand that at Kinmel there were 365 windows, 52 chimneys and 12 outside doors. I might be wrong there though, check it out.

He was keen on the Arts and Crafts movement with wrought iron work on the fencing and roof work. There is extensive use of oak panneling with linen fold patterns and the main staircase at Cloverley and, I believe, at Kinmel, were quite elaborately made.

Cloverley exhibits carved finials on the newel posts and carved lizards on the top and bottom finials n the stairs. His signature was a series of "Nesfield pies", circular designs of flowers, usually all different, carved into wooden doors, sandstone panels, and beaten into lead roundels at Kinmel. These designs were not new as I have come across them in much older buildings, particularly at Moreton Corbet Hall, which was an Elizabethan Mansion near Shawbury, now in ruins.

I understand he never married and died in his late fifties. Cloverley Hall was his first major work, possibly gained by winning a young architects' competition to design a horse trough for the square outside Heywood's Bank in Norris Green in Liverpool.

Heywood's Bank became Martin and Heywood's, then was totally absorbed in Martins Bank which was taken over by Barclays many years ago, but the Norris Green branch of Barclays is known as the Heywood's Branch.

bottom of page